Agora – Lev Bratishenko

An interview with the Canadian Centre for Architecture

Following the idea of the Agora, MESURA introduces a series of talks by people in the field, offering a different point of view on every day concepts. This time we invite Lev Bratishenko, Curator, Public at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal, founded in 1979 as a new type of cultural institution, with the aim of increasing public awareness of the role of architecture in contemporary society and promoting research in the field —Sharing some of his insights on the current moment of “Reset”, due to the global pandemic, and the role of the architect in times of change.

To Produce Concern Means You Don't Pretend to be Neutral

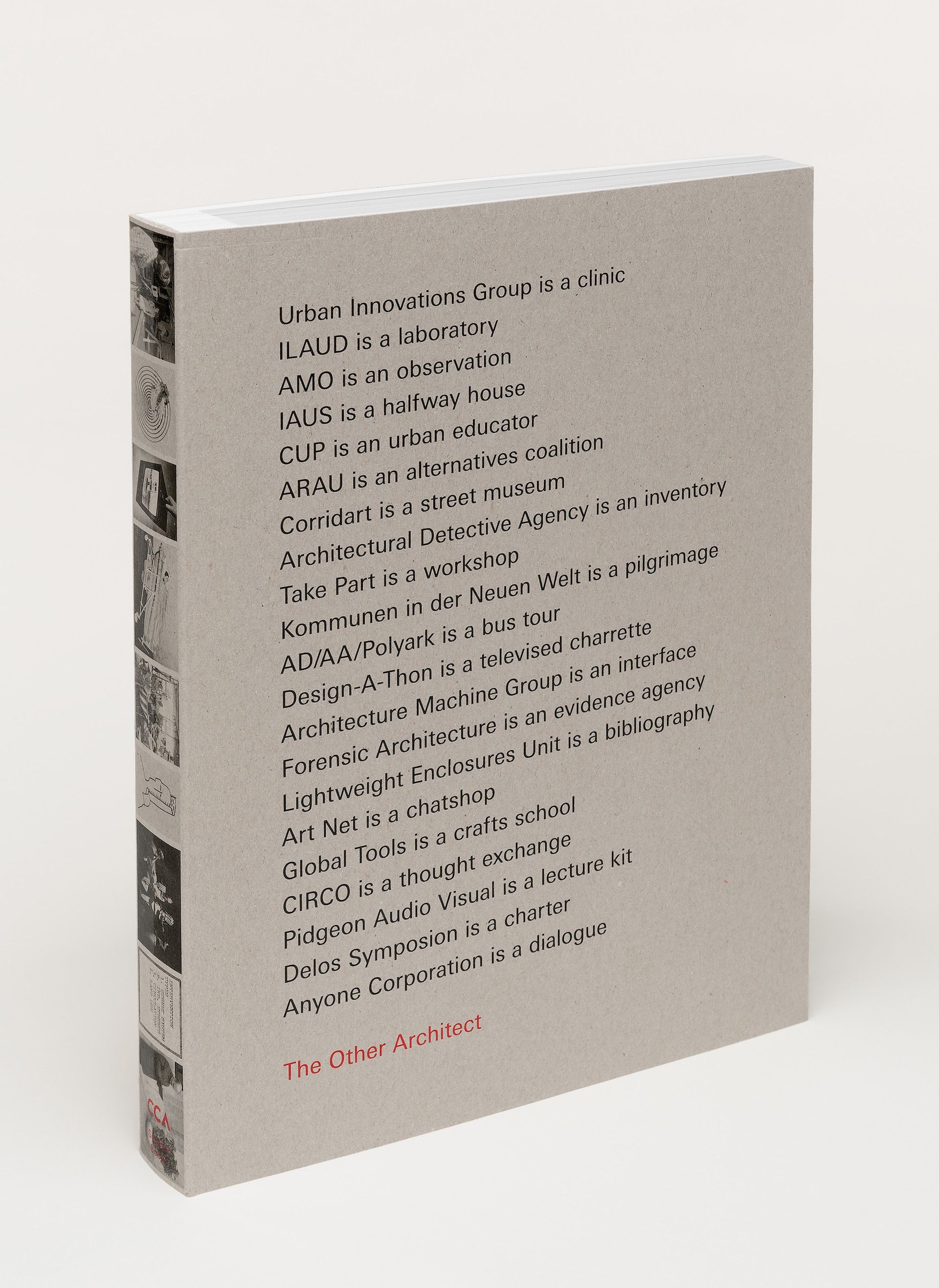

← Image: The Museum is Not Enough (Front Cover). This publication was conceived as the first volume of a yearly magazine, with which the CCA explores urgent questions defining its curatorial activity. (CCA/Sternberg Press, 2019) © CCA

MESURA

The CCA constantly asks questions, to itself as an institution and to its audience, always trying to find new ways of thinking. You’re a very active and dynamic institution. There’s books, research programs, residencies, “How to” workshops, aside from the exhibitions and public events.

In your book “The Museum is Not Enough”, the CCA looks for the grey areas, which is where we find questions, not answers. In MESURA, our philosophy is to design for the unknown, which is a very similar concept. What questions are you asking yourself today, in regard to the current situation, which feels more grey than ever?

LEV

I would say we are by design an unsettled institution, always asking ourselves what kind of institution we want to be, which means being ok with being uncomfortable. I think we have some productive contradictions here. First, because we are actually a stable institution, with a very solid foundation, an incredible Collection, and a history of remarkable projects. So we are large enough to do important projects, but small enough to be agile.

And there was a clear perspective from the very beginning, when Phyllis Lambert founded it in 1979, that CCA was always a research center for architecture, which means we are interested in what architecture can and should be, rather than just reflecting the current conditions as they happen to be. The actual mandate is super clear: to make architecture a public concern. We’ve recently expanded on this in the first nine lines of thinking in the publication The Museum Is Not Enough.

To produce concern means you don’t pretend to be neutral. It means having an agenda and putting it out there. It means we are always addressing why we are doing a certain project, and why in specifically this way, as an exhibition or event or publication, all the way through to how each of those formats is designed. It means being a bit intense.

View of the CCA from a window of Hôtel Du Fort, Montreal. Photograph by Naoya Hatakeyama. Collection CCA. Gift of the artist. ©Naoya Hatakeyama

“To produce concern means you don’t pretend to be neutral. It means having an agenda and putting it out there.”

← Image: Our Happy Life: Architecture And Well-Being in The Age of Emotional Capitalism, Edited by Francesco Garutti. (CCA/Sternberg Press, 2019) © CCA

LEV

Let me give you two examples. Last year we presented a project called Our Happy Life: Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism, curated by Francesco Garutti, CCA’s Curator, Contemporary Architecture. Our Happy Life investigated the boom after 2008, after the financial crisis, of quantified emotions as a political tool. Basically, governments realized that GDP was a bad indicator of success, and it was even worse at predicting trouble, so there was an explosion of studies, consultancies, metrics, and annual reports that claimed to measure subjective emotions. The most famous is the annual UN World Happiness Report.

And we were interested in what this means for architecture. Are these new values and the systems around them are actually somehow the designers of our cities today?

The project developed through parts with different goals. In addition to the exhibition, there is an online web issue Will Happiness Find Us, and a publication with Sternberg Press, which added many voices. And we produced a series of interviews where we posed questions directly to architects like Bruther and Reinier de Graaf.

And we also invited some people for a drink in the galleries, at the very end of the exhibition. Not architects, because we wanted to have a different kind of conversation, and we filmed this drink. It’s kind of a TV talk show and you can see us struggling between enjoying ourselves and not drinking too much. And the question we asked was: is happiness really the best goal for our cities? Happiness is a transitory, temporary, highly subjective and culturally specific construction. Is happiness even possible to talk about in some consistent way? I titled the conversation: Should We Worry?

Another example of the questions we’re asking now is an experimental project we were developing before the lockdown. It’s part of an ongoing research into individualism and how it impacts our idea of space. And one of our first questions is always: who do we want to talk to?

We launched this question as an open call last month. It’s called Is There An Expert In The Room—aged 13-16? And this is the first project we have ever done that approaches teenagers as experts. We see teens as digital natives, online since birth, basically, and also raised with much more awareness (than I was, anyway) of ecological fragility and our complicity in climate change. They can have really clear views, and be incredibly committed; I guess Greta Thunberg is the best example of this. And, at the same time, they live in quite odd and specific conditions. I mean, teens inhabited a condition of semi-lockdown before we all had to live in it. As a teen you are not an adult, you negotiate privacy and independence with your family, but you don’t normally have a choice to live at home, whatever the compromises. So maybe you have your own room that you can kind of control, but your movement and travel are limited, and your social life is almost entirely digital. This sound familiar yet?

Installation View: Our Happy Life: Architecture And Well-Being in The Age of Emotional Capitalism, An Exhibition Within an Exhibition, Curated by FRANCESCO GARUTTI, Presented as Part of Twelve Cautionary Urban Tales, at Matadero, 2020. Photo: Nuno Cera

“So what architecture can do is offer a model of deep contingency, a super dependence on others. Because we all know that the best projects come out of a complex process of care—of negotiation.”

The Best Projects Come Out of a Complex Process of Care—of Negotiation

← Image: The Other Architect: Another Way of Building Architecture, Edited by Giovanna Boars (CCA/Spectator Books, 2015) © CCA

MESURA

The current heath crisis has lifted some sort of fog. We already knew that our present was flawed, and that our future is unknown. Yet now, the fog of the everyday, of blind routine, has lifted, and we are confronted with the unknown –Because nobody really knows what will happen from here on out.

What kind of people, what kind of figures and roles, can counter that anxiety? Do we as architects have a role to play there?

Lev

Like, does architecture have some role to manage anxiety? The question is intriguing, but I have to say I think the answer is no. There is too recent and too long a history of architect experts claiming to know what is best for society, and building all kinds of problematic agendas and projects out of hubris.

What is your motivation as an architect? I mean, if you are doing something out of ego, an urge to prove that architecture is still relevant, than how careful or thoughtful can you really be? So I am skeptical of anything that smells like architecture trying to reassert itself, to reclaim some 20th century heroic status. I really recommend reading an amazing essay by Rebecca Solnit “When the Hero is the Problem”. It doesn’t address architects explicitly, but I think every architect should read it.

There is a lot of understandable anxiety that architects have lost some prominent position, but if you look at it carefully, this was always a myth; there was always the power of the client, the power of the banks, the legal codes, the building codes, political demands; Architecture depends, as Jeremy Till put it in his book. It always has.

This only seems like a weakness if you dream of acting as a kind of power demon imposing your brilliant vision on a city. There was a recent article about how American politicians keep doing video calls with Robert Caro’s biography of Robert Moses in the background. This is quite revealing.

But what can seem like weakness is really strength. In a highly interconnected world, a practice like architecture that operates always with others, between many experts, able to constantly shift perspectives, synthesize different approaches, speak different languages, etc. This are incredible skills! But they are very different from this historic image of the architect, the great master, so huge that all the people behind him (it’s always a him) disappear. (This myth persists in part as a survival mechanism under capitalism.)

We live in a deeply individualistic culture. It seems that for the past 40 years (at least) we’ve been told that the summit of accomplishment is self-sufficiency. This is absurd. Humans are some of the most social and the most interdependent animals. But it’s interesting that both the left and the right fall into this seductive trap: for example, the kind of drop out hippie communities that shut themselves out under literal domes, and on the right, with the development of wealthy nomads, no fixed address but many passports (didn’t Elon Musk just announce he’s selling all his houses?) The neoliberal superman is just a floating bank account open to all opportunities, and able to leverage an international infrastructure of care (nannies, concierges, maids, etc.) Look where this has got us?

So what architecture can do is offer a model of deep contingency, a super dependence on others. Because we all know that the best projects come out of a complex process of care—of negotiation.

There’s a breathtaking essay by Paul Preciado on Artforum, called “Learning from the Virus” and I won’t summarize it, but it ends with a call to unplug, and to learn from the ways that minorities have struggled against oppressive systems.

I think the architectural implication is a turn to radical humility: to learning from the kinds of practice—historical and contemporary—resist heroism, resist extraction and endless growth, resist racism. How to be architects and do no harm? That’s the question.

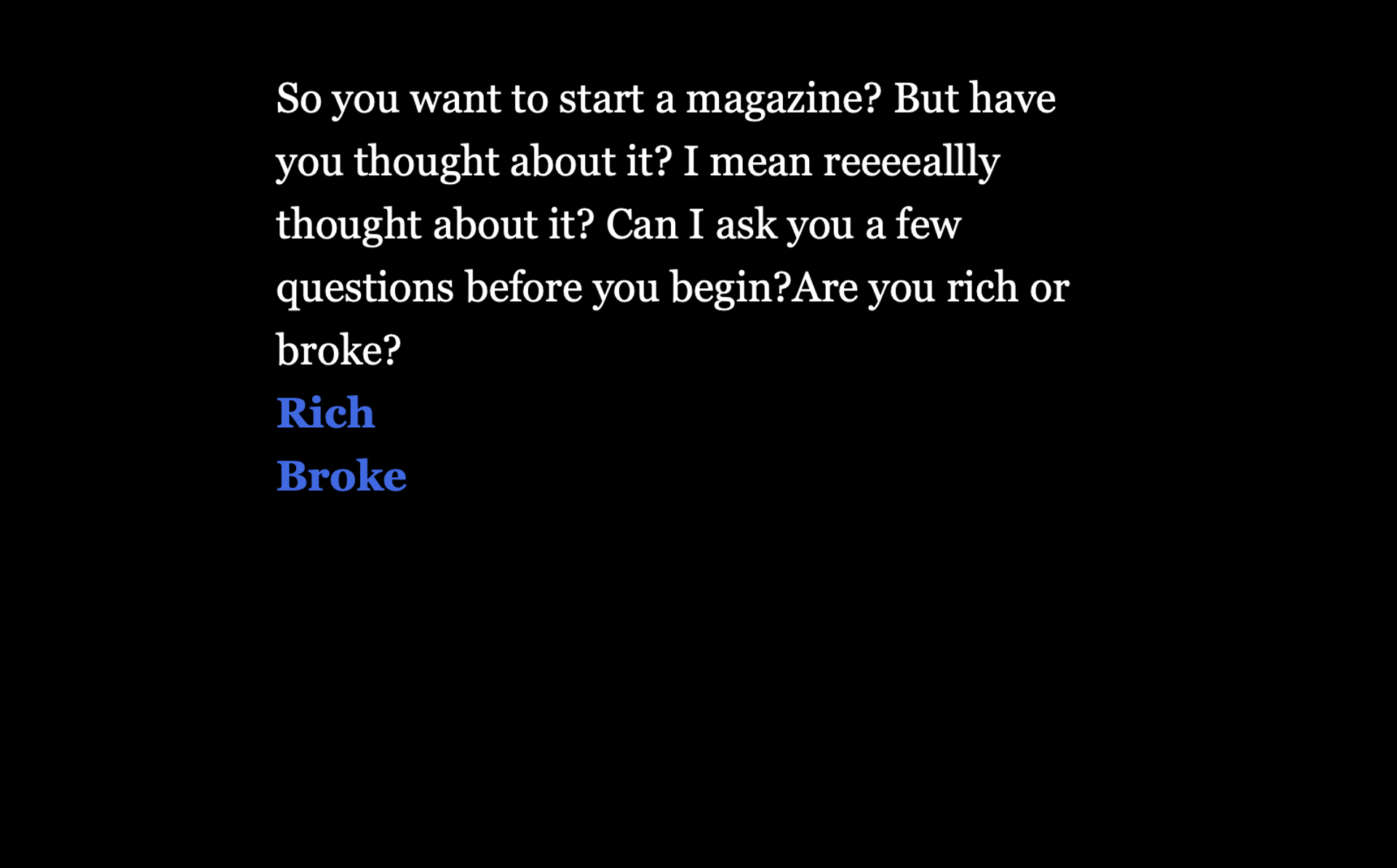

“How To” is a series of accelerated annual residencies that bring together small teams at the CCA to make a new tool to address a specific opportunity or need. 2018's edition 'How to: Not Make an Architecture Magazine' produced a manual for avoiding publishing. Directed by Lev Bratishenko, CCA curator, Public, and Architect and Writer Douglas Murphy. © CCA

“I think the architectural implication is a turn to radical humility: to learning from the kinds of practice, historical and contemporary, that resist heroism, resist extraction and endless growth, resist racism. How to be architects and do no harm? That’s the question.”

Our Society Has to Change in Order to Encourage Other Kinds of Architects

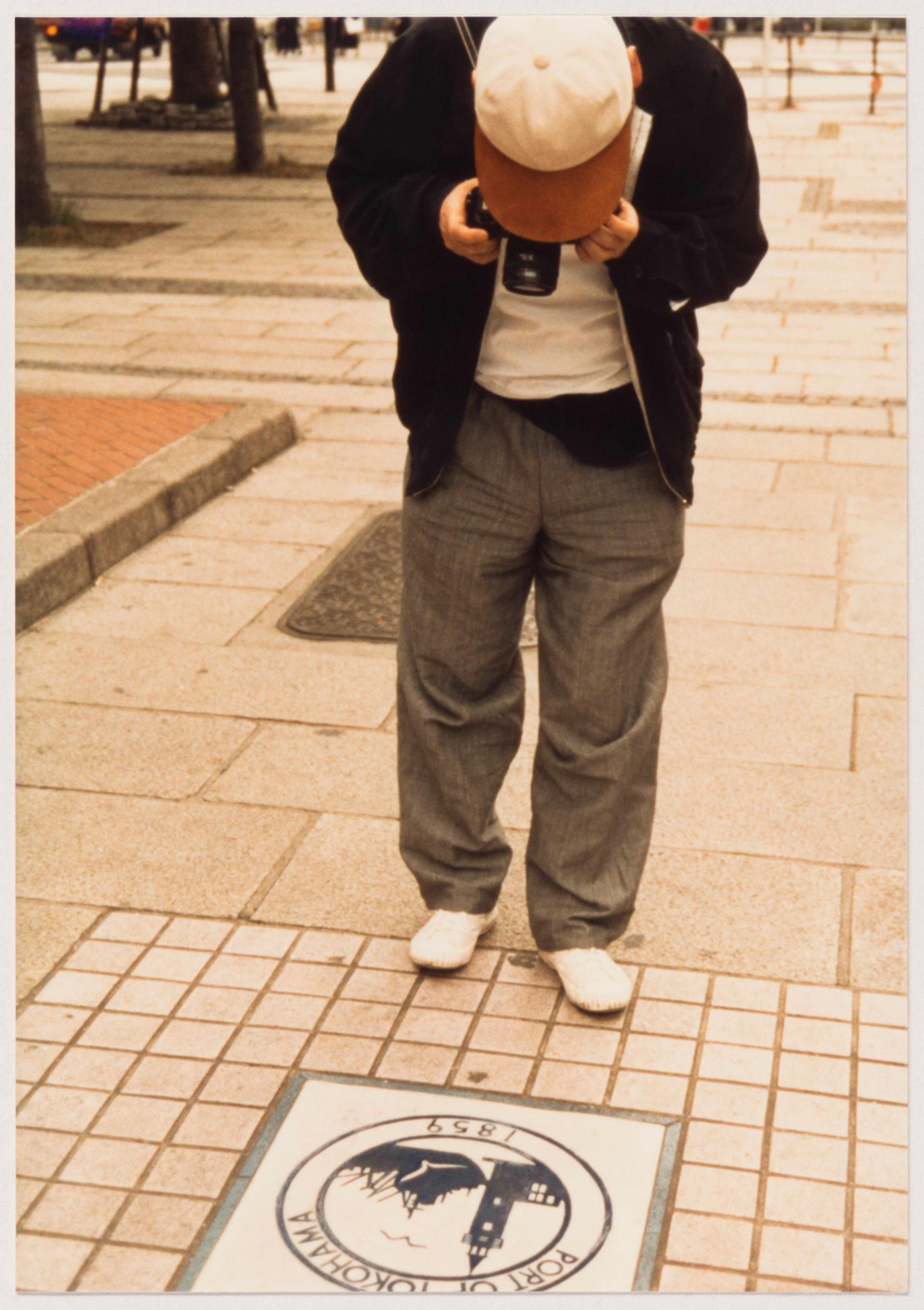

← Image: Shimbo Minmai, an Illustrator, Cartoonist, And Member of Rojo, at Work Documenting The Street, Ca.1985. Photography by Tetsuo Matsuda © The Rojo Society

MESURA

Like the CCA, we understand the new architect as more than a builder. We learn from different kinds of fields, and our role varies greatly according to particular projects, users and purposes. Sometimes we act as mediators, sometimes we become film makers or editors, or educators etc etc. The one enriches the other, and it has provided us with new ideas, tools and methods to approach our field.

How would you describe architecture or the architect, beyond the idea of building?

LEV

A few years ago we did a project called The Other Architect, curated by Giovanna Borasi, who is now CCA’s new director. The Other Architect looked for examples, historical and contemporary, of architects producing a cultural agenda without using built form. We chose 22 projects that reflect different ways of looking critically at the role of the architect, its responsibilities and capacities.

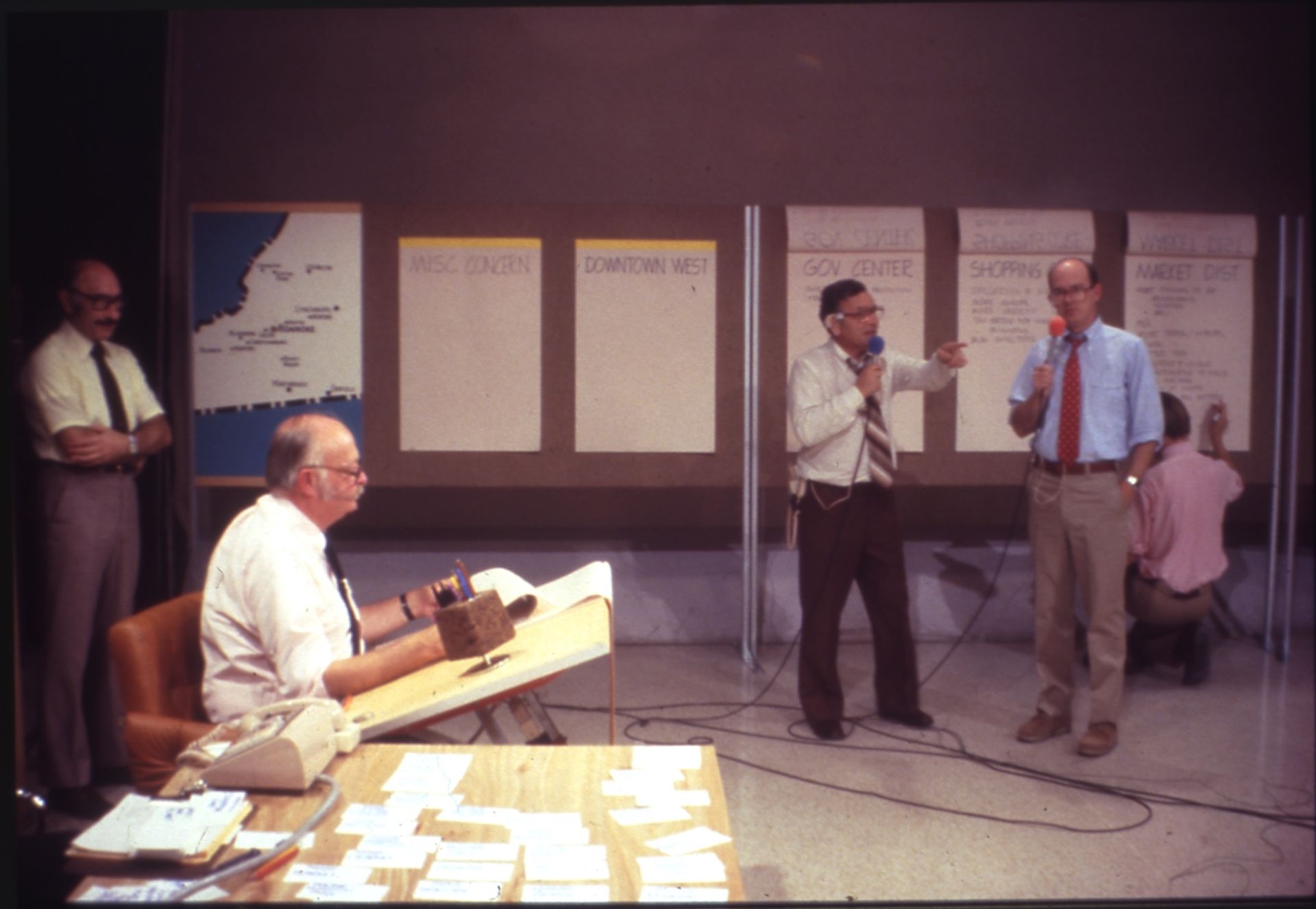

“Design–a–thon” was a series of public television programs produced by Moore Grover Harper in Connecticut, that included Charles Moore. They used techniques from game shows, telethons, news broadcasts, talk shows, to involve communities in projects. You could call in during the broadcast and tell them to move a building, and they would try it out, live. It’s still an exciting example of using technology to change the relationship between architect, client, and public.

Another case was the Architectural Detective Agency, which was this ad hoc group that formed to document central Tokyo. They took photographs, often trespassing to do it; they conducted interviews with architects or their families; they collected everything from drawings to newspaper articles into archives. It was a huge work that produced a new understanding of what was already there, at a time when modernist redevelopment depended on ignoring or dismissing the existing urban fabric.

Both projects had clear agendas that were exciting for us. But I think the general point is how challenging the traditional role of architects as producers of buildings, a wider range of field of action appears. Because if you limit yourself to working only through buildings, you are actually choosing a reduced cultural influence.

A point that would be interesting to focus on now, if we were doing the project again, is how to sustain this kind of practice. Many interesting architects survive on an income in academia, for example, so that they can produce research that wouldn’t be supported by the normal commercial channels. This is something we’ll be researching in public soon, with a new series of talks called It’s Only Money.

But there is a further implication that it goes beyond architecture. Instead of always asking, how do we twist ourselves to make possible the kinds of work we want to do, why not honestly face facts? It is our society that has to change in order to encourage Other kinds of architects, so there’s a political project here that’s only lightly architectural.

And making this demand for change means becoming allies, making connections with all the other people who have unfulfilled ambitions for their professions; as well as all other kinds of work, and especially the kinds of work that is often not recognized as work. Facing this need for change means admitting a need for political action, personally and professionally, and I think that is very important.

Charles Moore drafting live during a television broadcast of Roanoke Design '79, while host Ted Powers and Floyd address the camera. 1979 Design–a–thon. Centerbook Architects And Planners Records. Manuscripts and archives, Yale University Library © Centerbook Architects And Planners

An architect from Moore Grover Harper works while on display in the window of the River Design Dayton Storefront office on Gibbons Arcade, 36 West 3rd Street, Dayton, Ohio. 1976. Design–a–thon. Centerbrook Architects and Planners Records. Manuscripts and Archives, YALE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY © Centerbook Architects And Planners

“Once you have seen what your “normal” life costs, in terms of cruelty to other people and to the ecology, how can you go back? Like, once you’ve seen the air in your city clean for the first time in your life, you’ve seen the sun—will you forget it so easily?”

We Have to Become Very Demanding

← Image: Partial view of the sough facade of the CCA showing the Paul Desmarais Theatre and the Conservatory. Photograph by Naoya Hatakeyama. Collection CCA. Gift of the artist © Naoya Hatakeyama

MESURA

Covid19 has made our world, come to a halt. Sometimes it feels like we’ve pushed a reset button, and newspapers are filled with articles on “The new normal”. Our standards, our rules have actually changed —Alternatives are arising, which is probably the only beautiful thing about a crisis.

How does the CCA, how do you see this idea of the new normal? And more importantly, how can we use this momentum, in order to actually flip the way we do thing?

LEV

Right now you see a rush to re–open. It’s incredible that so many countries (including Canada) are reopening while the infected cases and the death toll are holding steady or even rising. So we have an unusually clear and painful proof of the system of values we live in. What lives matter and what lives are expendable. What Preciado calls the “horizontal workers” people who were able to work remotely, and who will now have expanded leisure and social options. And what he calls “vertical workers”, the people who had to keep working, keep taking crowded public transit, who have been forced to risk their lives so that we have grocery stories, online shopping, whatever (not to mention all the questionable “essential” businesses that were allowed to stay open.) They will see no change and will actually face an even further increased risk. This is very stark evidence.

So I hope the new normal includes this clarity but I think we must fight to preserve it. It’s never been clearer what “normal life” costs other humans and non-humans. So, in a way, a de-normalization process is needed. Bruno Latour published a great short essay in March where he asks people to list what they want to come back and what they don’t want to come back, and then to consider what those positive and negative desires imply for other people.

Once you have seen what your “normal” life costs, in terms of cruelty to other people and to the ecology, how can you go back? Like, once you’ve seen the air in your city clean for the first time in your life, you’ve seen the sun—will you forget it so easily?

We have to make sure that we don’t. And we can see many tentative steps, like Milan or Paris announcing policies to reduce cars. These are nice, but we should think bigger. The state of exception has produced a lot of interesting things. Suddenly, we have proof that all the homeless in a city can be housed; that there were always enough hotels and empty apartments for them. The issue was not capacity but who controls the capacity. We have proof that rent can be stopped. That evictions can be stopped. That migrants can be treated like citizens, as happened in Portugal; or that universal basic income is possible, as I understand is being developed in Spain. A lot of things have appeared in the real world that, a few months ago, we were told we couldn’t have.

Most of these positive examples are still deformed, because they are still products of a system designed to produce money instead of life, but I think that their reality, even if its temporary, must change our expectations of what is possible. We have to become very demanding. We have to refuse “this is as good as it can be”.

When entering the CCA, a quote by Gordon Matta–Clark: Here is what we have to offer you… confusion guided by a clear sense of purpose. Photograph by Filippo Romano from the series “Uncollected” at CCA. CCA Collection. Gifts of the artist. © Filippo Romano

BIO

Lev Bratishenko (Moscow 1984) is a writer and the inaugural Curator, Public at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). Recent curatorial projects include the “Come and Forget” series proposing benevolent acts of mass amnesia, and “How to”, an annual workshop for architectural and curatorial provocation: “How to: not make an architecture magazine” 2018, “How to: disturb the public” 2019, and “How to: reward and punish” 2020. Bratishenko has been contributing to CCA exhibitions, publications and online projects since 2007, including curating “The object is not online” in 2010 and co–editing “It’s All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment” in 2016. He’s written over 170 articles and reviews of architecture, classical music and opera.